This blog post was written by Liam Dempsey. Liam is currently working as a legal researcher in the Law Reform Commission and was the principal legal researcher on the Commission’s recently published Report on Suspended Sentences (LRC 123-2020). He has an interest in sentencing law and policy, both from a legalist and criminological perspective and has previously written about implicit judicial sentencing bias in the context of socioeconomically deprived offenders, and the duty of District Court judges to give reasons at sentencing.

NOTE: The views expressed in this post are those of the author, Liam Dempsey, and not those of the Law Reform Commission.

To what extent should an offender’s “dysfunctional background” (terminology as per The People (DPP) v Fitzgibbon [2014] IECCA 12 at para 9.5] be deemed relevant at sentencing? The principle of proportionality requires sentencing courts to impose a sentence that is proportionate to both the gravity of the offence and the personal circumstances of the offender. When constructing this proportionate sentence, the sentencing court should first assess the gravity of the offence, by reference to the harm caused and the offender’s moral culpability. The court should then make the appropriate discount from the “headline sentence” to account for the offender’s personal mitigating factors which justify a reduction in the severity of the sentence.

Returning to the initial question, traditionally, Irish appellate courts have held that an offender’s “dysfunctional background” is a relevant personal mitigating factor and should serve to reduce the severity of the sentence. However, recently the Court of Appeal has established that an offender’s “dysfunctional background” may be relevant to the assessment of the gravity of the offence, and in particular the moral culpability of the offender.

The concept of moral culpability in the Irish sentencing case law has traditionally centred on the state of mind or mens rea of the offender at the time of the offence. However, as Ashworth notes “culpability is a wider issue than cognition, as represented by the two legal terms of intention and recklessness, and extends to a wider range of volitional and situational factors” (2012, p. 121). The Court of Appeal has embraced this broader conceptualisation of moral culpability by introducing the concepts of “intrinsic moral culpability” and “actual moral culpability”. The offender’s intrinsic moral culpability refers to whether the offence was committed intentionally, recklessly or negligently, while his or her actual moral culpability is to be adjudged by reference to broader circumstantial or behavioural factors relevant to the commission of the offence (The People (DPP) v Shaun Kelly [2016] IECA 204).

Significantly, the Court has held on a couple of occasions that an offender’s “dysfunctional background” is relevant to the assessment of his or her actual moral culpability and may serve to reduce the gravity of the offence. In The People (DPP) v Leon Byrne [2018] IECA 120, the Court of Appeal held that the offender’s difficult upbringing, involving “neglect, criminality, homelessness and violence” and consequent descent into drug and alcohol addiction was a factor mitigating his actual moral culpability. Similarly, in The People (DPP) v Stephen Comey [2018] IECA 161 the Court recognised the offender’s “significant and chronic addiction as … a mitigating factor tending to reduce culpability”.

It could be argued that there is little practical difference between treating an offender’s “dysfunctional background” as a conventional mitigating factor or as a mitigating factor bearing on moral culpability. However, it is one thing to say that an offender’s “dysfunctional background” forms part of his or her personal circumstances and should, therefore, in line with the principle of proportionality, serve to reduce the severity of the sentence. It is quite another, at least in principle, to say that an offender’s “dysfunctional background” renders him or her less morally blameworthy for the offending behaviour and, by extension, reduces the gravity of the offence.

Indeed, this contextualised formulation of moral blameworthiness challenges well-established legal assumptions about free-will and individual choice, assumptions which have been described as “universal and persistent in mature systems of law” (People v. Wolff 3 94 P.2d 959, at page 979). The doctrine of free will has ensured that considerations such as social and economic deprivation have largely (although, see Bazelon, 1981; 1976) been dismissed as irrelevant to the question of criminal responsibility by the judiciary (Southwark London Borough Council v Williams) and academics (Morse, 1977; 2011). As Hudson puts it:

“Legal reasoning seems unable to appreciate that the existential view of the world as an arena for acting out free choices is a perspective of the privileged, and that potential for self-actualisation is far from apparent to those whose lives are constricted by material or ideological handicaps.”

(Hudson, 1994, p. 302)

However, perhaps it is justified that “the [substantive] criminal law treats man’s conduct as autonomous and willed, not because it is, but because it is desirable to proceed as if it were” (Packer, 1968, pp. 74-75). After all, at the trial stage of the process, the determination to be reached as to criminal responsibility is binary in nature – guilty or not guilty. Conversely, the sentencing court, and particularly in sentencing regimes such as our own – underpinned by the “just deserts” of proportionate punishment – is primarily concerned with assessing the degree of blameworthiness that should be attributed to the offender for his or her unlawful acts (Ashworth and Von Hirsch, 2005, p. 134).

Nevertheless, despite the less binary nature of the sentencing stage of the criminal process, notions of free will and choice are still very much central to the punitive philosophies of retribution and deterrence, both of which have been established as forming two out of the three main sentencing aims in Irish law [Law Reform Commission, Report on Suspended Sentences (LRC 123-2020) at paras 3.18 – 3.21]. Deterrence theory is grounded on the premise that all human beings are rational actors with the capacity to weigh up the likely costs and benefits of engaging in criminal behaviour (Murphy, 2013, p. 219). Deterrence theory thus purports to provide moral legitimacy to the State, through the medium of the criminal courts, to punish persons who – as rational agents – have transgressed the criminal law.

Arguably the most influential subset of retributive theory has been the “benefits and burdens” argument, which posits that punishment is a just and proper response to a past offence, since it restores that “fair” balance of benefits and burdens in society which crime disturbs. When a person commits a crime, he or she benefits from others not breaking the law, while the rest of society is burdened at the hand of the criminal act. Punishment is, thus, society’s way of restoring the “social equilibrium” (see: Murphy, 2013; Duff, 1986 pp. 206-08).

Both theories of punishment, and in particular retributive theory, in seeking to provide moral justification to the State to punish, proceed on the assumptions that: criminal behaviour is an act of free will on the part of the offender, and; the criminal act disturbs an otherwise equal and fair society (O’Riordan, 2002, pp. 565 -566). Murphy (2013, pp. 241-242) points out the paradox inherent in these assumptions, noting that “retributive theory, though formally correct, is materially inadequate. At root, the retributive theory fails to acknowledge that criminality is, to a large extent, a phenomenon of economic class”.

These criticisms do indeed call into question the moral underpinnings of the Irish sentencing system. However, it should be noted that the traditional paradigms of retributive and deterrence theory are concerned with the question of “Why Punish?” In contrast, the recent line of case law of the Court of Appeal is, within the framework of the proportionality principle, concerned with the question of “How much to punish?” Therefore, it may be a step too far to assert that these decisions have the potential to place the Irish sentencing system on a sounder theoretical justificatory footing. Nevertheless, this line of case law should be praised for, whether advertently or inadvertently, acknowledging the reality that an individual’s circumstances and upbringing constrain the extent to which his or her criminal behaviour can be said to be an exercise in free will.

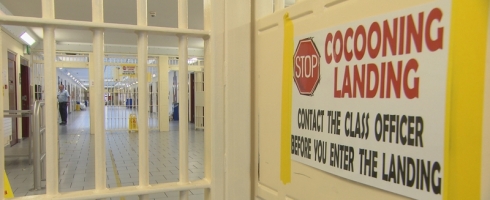

This becomes all the more important when we consider the empirical literature demonstrating that the social make-up of the Irish penal population is overwhelmingly made up of persons coming from the most socioeconomically deprived areas of Ireland (O’ Mahony, 1998; O’Donnell et al, 2008; IPRT, 2012; Bacik et al, 1998). O’ Mahony’s study of prisoners in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, revealed that a third of interviewees hailed from inner-city corporation flats, with nearly all of the remaining interviewees coming from low-quality social housing. O’Mahony’s study also revealed that only 9% of interviewees grew up in a home where one of the parents was employed in a job which could be described as providing a reasonable standard of living (O’Mahony, 1998, pp. 620 – 625).

The extent to which Irish sentencing courts at first instance, particularly the Irish District Court, will embrace this development remains to be seen. O’ Malley (2011, pp. 120-123) notes how one of the main limitations of appellate guidance is its failure to transmit its jurisprudence to lower sentencing courts. Further, research in Ireland suggests that Irish District Court judges’ sentencing decisions may be informed by unconscious socioeconomic bias (Dempsey, 2016; Bacik et al, 1998), manifesting in a belief that the causes of crime are internal, stable and controllable, as opposed to a result of circumstance (O’Donnell, 2010; O’Nolan, 2013, pp. 94 – 95). Nevertheless, it is hoped that this recent line of case-law has a tangible impact at the coalface of the Irish sentencing system, where the incontrovertible link between crime and poverty is acutely apparent. As O’Nolan (2013, pp. 94-95), in her observational study of the District Court, noted: “most persistent offenders observed were vulnerable individuals with chaotic lifestyles characterised frequently by homelessness, drug and alcohol abuse, mental health issues and low levels of education”.

References

Ashworth, A. (2012) Sentencing and Criminal Justice 5th ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Ashworth, A. & Von Hirsch, A. (2005) Proportionate Sentencing: Exploring the Principles (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Atiq (2013) E.H. How folk beliefs about free will influence sentencing: A new target for the neuro-determinist critics of criminal law. New Criminal Law Review 16 (3) 449-493.

Bacik, I. (1998) Crime and Poverty in Dublin: An Analysis of the association between community deprivation, District Court appearance and sentence severity in Bacik, I., O’Connell, M (eds) Crime and Poverty in Ireland (Dublin: Round Hall Sweet and Maxwell)

Bazelon, D.L. (1981) Foreword – The Morality of the Criminal Law: Rights of the Accused. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 72 (4) pp. 1143-1170.

Bazelon, D.L. (1976) The Morality of the Criminal Law. Southern California Law Review 49, p. 385.

Dempsey, L. (2016) ’The Greater of Two Evils? – Examining Sentencing Variations in the Irish Courts: A Critical and Methodological Appraisal. UCD Law Review 16 pp. 163-206.

Irish Penal Reform Trust (2012) The Vicious Circle of Social Exclusion and Crime: Ireland’s Disproportionate Punishment of the Poor (Position Paper, Shifting Focus).

O’Donnell, I. (2007) When Prisoners go Home: Punishment, Social Deprivation and the Geography of Re-integration. Irish Criminal Law Journal 17(4) p. 3.

O’ Donnell, I., Healy, D. (2010) Crime, Consequences and Court Reports. Irish Criminal Law Journal 20 (1) pp. 2-7

Ian O’Donnell, I., Eric .P. Baumer, E.P., Hughes, N. (2008) Recidivism in the Republic of Ireland. Criminology and Criminal Justice (8) p. 123.

Duff (1986) Trials and Punishments (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Von Hirsch, A. (1993) Censure and Sanctions (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Jones, M. (2003) ‘Overcoming the Myth of free will in criminal law: The true impact of the genetic revolution’. Duke Law Journal 52 pp. 1031-1053.

Law Reform Commission, Report on Suspended Sentences (LRC 123-2020)

Morse, S.J. (1977) The Twilight of Welfare Criminology Faculty Scholarship. Paper 1293.

Morse, S.J. (2011) Severe Environmental Deprivation (AKA RSB): A tragedy not a defense. Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review (2) pp. 147-173

O’Malley, T. (2006) Sentencing; Towards a Coherent System (Dublin: Round Hall).

O’Mahony, P. (1998) Punishing Poverty and Public Adversity in Bacik, I., O’ Connell, M. (eds), Crime and Poverty in Ireland (Dublin: Round Hall Sweet and Maxwell).

Murphy, J. (2013) Marxism and Retribution. Philosophy and Public Affairs 2(3) 218

O’ Nolan, C. (2013) The Irish District Court: A Social Portrait (Cork: Cork University Press).

Packer, H. (1968) The Limits of the Criminal Sanction (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

O’ Riordan, P. (2002) ‘Punishment in Ireland: Can we talk about it?’ in O’Mahony, P. (ed) Criminal Justice in Ireland (Institute of Public Administration).

Robinson, P. (2011) Are we responsible for who we are? The Challenge for Criminal Law Theory in Defences of coercive indoctrination and “Rotten Social Background”. Alabama Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Law Review (2)(2) p. 53.

Case Law

The People (DPP) v Leon Byrne [2018] IECA 120.

The People (DPP) v Cawley, Court of Criminal Appeal, 22 March 1999.

The People (DPP) v Stephen Comey [2018] IECA 161.

The People (DPP) v O’Dwyer [2005] 3 IR 134).

The People (DPP) v Fitzgibbon [2014] IECCA 12.

The People (DPP) v Hall [2016] IECA 11.

The People (DPP) v Shaun Kelly [2016] IECA 204.

The People (DPP) v MAF [2016] IECA 14.

The People (DPP) v McCormack [2000] 4 IR 359.

The People (DPP) v TB [2016] IECA 250.

(People v. Wolff 3 94 P.2d 959).

Southwark London Borough Council v Williams [1971] Ch 734.